The last decade of the internet gave rise to an 'aggregators' vs. 'arms dealers' dichotomy across various e-commerce categories. The 'aggregator' centralizes control, charging high fees to suppliers for distribution advantages while restricting access to critical information. The 'arms dealer' empowers capable and competent businesses with powerful tools to reach and retain their most loyal customers directly without an intermediary, sacrificing the aggregator's powerful network effects and convenience to the consumer. Think Amazon vs. Shopify or DoorDash vs. ChowNow.

The next decade of innovation will disrupt both categories with a final alternative; decentralized platforms and protocols made possible by blockchains. These next-generation platforms inherit the best qualities of 'aggregators' and 'arms dealers', representing a paradigm shift in how entrepreneurs build networks and how users witness the upside of a network’s success.

“Whereas most technologies tend to automate workers on the periphery doing menial tasks, blockchains automate away the center. Instead of putting the taxi driver out of a job, blockchain puts Uber out of a job and lets the taxi drivers work with the customer directly.” - Vitalik Buterin

Sufficient decentralization

A consumer marketplace achieves sufficient decentralization if supply and demand can find one another and engage in a transaction independent of a third party. When sufficiently decentralized, suppliers and consumers can reach one another without being subject to an arbitrary set of rules (fee structures, data rights, etc.) defined by one central authority. Disintermediating the central authority requires an open protocol where developers are free to build multiple clients on top of a basic set of instructions that define the components of a transaction.

Different clients then define any given set of additional criteria for the experience that they intend to create. Decentralization ensures that a client is neither monopolistic nor rent-seeking. It establishes a market-based approach where the best ideas can compete on equal footing, and participants can freely adopt the client that best suits their needs.

These concepts closely resemble SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol). SMTP is used most commonly by email clients, including Gmail, Outlook, Apple Mail, and Yahoo Mail, where individual users have a unique identifier (email) but are free to exchange messages no matter which client they use (@gmail addresses are free to message @yahoo addresses). Companies can still make money by offering services, as Gmail obviously does. Still, the open protocol enables a competition of ideas on top of a more rudimentary set of concepts.

Sufficient decentralization for consumer marketplaces only requires three essential criteria: the ability to claim an identifier, engage in transactions under this identifier, and share information with other agents in the ecosystem.

Of course, consumer marketplaces do more than send transaction data between a buyer and a seller - the most straightforward web2 applications facilitate payments, send notifications, and recommend new products or services. These features would be difficult to decentralize, and dynamic consumer behaviors for feature requests would outpace any organization's capacity to decentralize said features. But more is needed to compromise sufficiently decentralized systems. Clients can still compete to deliver novel offerings on top of a protocol, just as Google, Yahoo, Apple, and Microsoft have done with SMTP.

A common misconception about web3 is the expensive costs of storing information on-chain. However, on-chain data storage is unnecessary for sufficiently decentralizing (if not wholly undesirable). A well-designed decentralized consumer marketplace platform will retain many qualities of web2 platforms (data storage and the ability to delete and update data at low cost), using web3 to decentralize ownership and control of the network. Until gas fees on blockchains hit pricing parity with traditional systems, this hybrid approach represents a future in which consumer marketplaces will be owned by their users without sacrificing affordability and usability.

The benefits of user-owned platforms are clear: they turn customers into citizens and push wealth outwards to the individuals who make the gears of modern economic life turn. So, why are people still using centralized consumer marketplaces? Until recently, entrepreneurs have been scratching their heads about three seemingly impossible-to-parse problems: scale, switching hosts, and coordination. Finally, there are reasonable approaches to solving each of these problems.

Scale

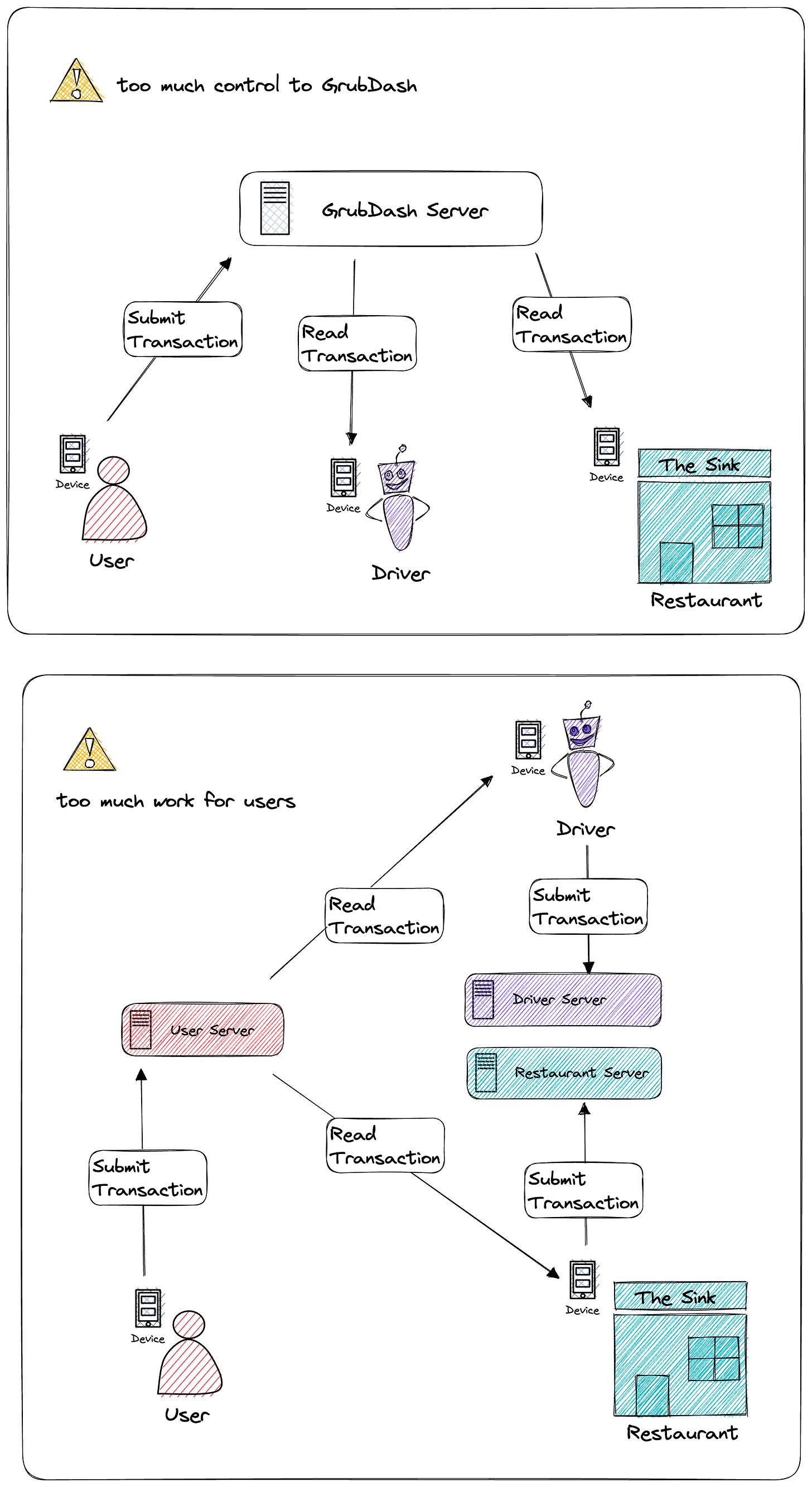

All marketplaces are a series of 'POST' and 'GET' requests through a centralized server. The entity that owns this central server has pricing power and administrative authority over all network participants. An easy way to solve this problem is to remove the centralized server, giving users options into where their information is stored: they sign their transactions using their preferred server with a public/private key pair, and their public key becomes their UID.

In practice, decentralized marketplaces should be free and straightforward to use. However, removing the centralized server reduces users' ability to store and fetch data freely. Although self-hosting can be automated and made simple, outsourcing this process to individual users would be a significant UX no-no. This expectation might work for a few use cases with a sophisticated user base, but better solutions exist to onboard the entire internet onto crypto rails.

The elegant middle ground here is to use a managed host. These smaller, more distributed intermediaries host, store, and fetch user data and can offer more complex features than individual users hosting their servers. Additionally, they can provide the convenience of onboarding users without any additional complexities.

The critical reader might complain that managed hosts don't represent the interests of individual users because they, too, can develop control or collude with other hosts to establish pricing powers. Over the long term, these predatory actors could bait and switch users in a way that benefits their short-term economic desires, causing problems for long-term stability and ultimately stagnating innovation because of a dissatisfied and disgruntled set of users who no longer trust the system.

A protocol that gives users independent control to change hosts solves these problems.

The game theory of imposing low host switching costs would have a rent-seeking host thinking twice before extracting from its users. Having an open-source code base that makes it easy to spin up a competitive offering would make collusion between hosts rare and unlikely. This system architecture would form an active dialogue among network participants and host admins, creating a long-term, sustainable, and aligned host-to-user relationship.

Switching hosts

When querying a system of managed hosts, any given user needs to know how to find the correct host to send transaction-related data, read information, and submit any requests. You can think of this simply in terms of a "username":"instance_url" key:value pair. This sort of record-keeping retains an up-to-date place for every network member to match their public key to their preferred host and will also include any location-specific information.

Let's take an example of food delivery in Boulder, CO, using a decentralized, managed host architecture. In this example, I am a user searching for nearby restaurants. I ask for nearby restaurants from a decentralized registry, finding @the_sink and receiving their host URL @the.hungry.buff, which I can then query to retrieve menu data, reviews, and more for @the_sink.

When I place the transaction, my payment processes and charges @the_sink a small 10% maintenance fee. If the admin for the @the.hungry.buff host decides later that they intend to charge a 30% maintenance fee to restaurants, @the_sink may determine that this is not a viable price structure for their business. As a result, they will intend to change hosts for a more suitable payment facilitation structure.

A decentralized registry that allows the restaurant to change its host protects them against a malicious host that intends to increase fees or remove its ability to transact, making it more likely for the restaurant to adopt a client application that has adopted the protocol. They retain the full power to modify the registry to point to a new host, and their data will switch over.

The emergence of smart contracts has enabled decentralized registries that allow controls for network members, which were previously challenging to establish. These smart contracts are designed to ensure that only the initiating user has the authority to modify their host URL, and the blockchain can provide effective conflict resolution in case two individuals attempt to register the same information simultaneously. Excitingly, projects like ENS have successfully implemented similar systems on Ethereum, demonstrating the enormous new potential for decentralizing consumer marketplaces.

The registry, then, is the only element requiring on-chain synchronization. All other actions can securely execute off-chain with a simple public/private key signature.

Coordination

In an economic system, coordination failure happens when a group of participants could have achieved a more desirable outcome but fail to because they cannot coordinate their decisions.

Our view of sufficient decentralization is all about coordination. It emphasizes solving problems through a federation of "local" units that congregate around the social and economic contexts more relevant to the decisions. Critically, local units are composable and interoperable, acting as legos or building blocks that can stack to a more globally influential scale.

Local and composable control distributes decision-making to those most impacted by the decisions. Thus, federations leverage a core principle of open markets: The people closest to a problem usually have the most knowledge of its solution. The most desirable economic equilibria are found by clustering and filtering this knowledge.

Conclusion

It's evident that centralized consumer networks profoundly influence our lives, and the limitations of these networks are increasingly apparent. However, advancements in cryptography and blockchain technologies offer viable solutions to achieve a desirable level of decentralization that grants more power and control back to individuals. Utilizing a hybrid off-chain/on-chain architecture, we can effectively scale next-gen consumer marketplaces that better serve the users they aim to support. Furthermore, innovative coordination mechanisms open a complex and exciting design space, creating new opportunities for exploration and experimentation.

If you want to work on these problems, view open roles at Palette Labs.

I love love love this thinking.

This said, to a few issues. Game theory almost always fails when the participants cannot be modeled precisely. The models almost always break down when confronted with biological, thinking beings. Those classically trained in Economics are rarely shown all the ways they do. I understand. Of course we want this pattern we feel we grasp to be understood by others, and it is hard to keep at the front of our brains that we are almost always dealing with incomplete information.

Whatever you are building, test as quickly as you can with real transactions, and then let's see where it goes! <3